How do we build memories?

Our minds are filled with memories that allow us to vividly re-experience events from many chapters of our lives. But memory is not just for remembering; rather, we use memory to guide future behavior. To do so, we abstract across related memories to find generalizable patterns that enable predictions. And in turn, this learned structure guides how we encode new memories. Employing behavioral, neuroimaging, neuropsychological, and computational methods, our lab explores the rich interactions between how the mind encodes unique events and abstracts across experience.

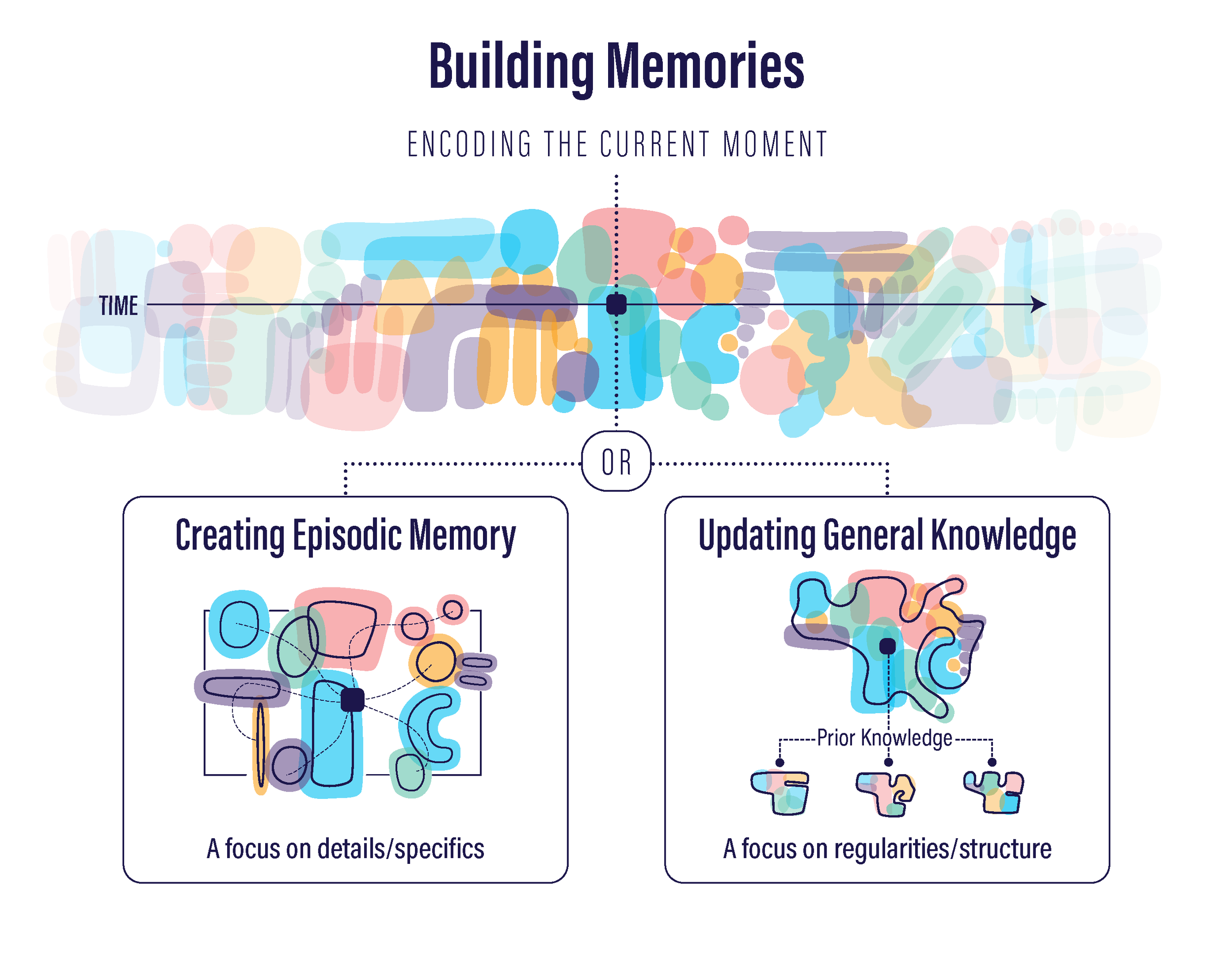

Our memories comprise not only unique moments (e.g., your episodic memory of what you did on your last birthday), but also more abstract information about what tends to occur (e.g., your general knowledge for what birthday parties are typically like). These two kinds of memory are computationally opposing: In order to remember the details of a specific experience, we must hold that memory as distinct from all other related experiences. Yet to tap into general knowledge, we must integrate across related experiences to promote abstraction.

Thus, each new experience poses a challenge for our mind and brain. On the one hand, we could focus on encoding the details of the experience, leading to the creation of a new episodic memory. On the other hand, we could focus on commonalities or regularities between this experience and other, similar memories, allowing us to integrate the experience with existing, related memories in the service of updating general knowledge. Our research focuses on the cognitive and neural processes that govern how we encode both the specific and general aspects of experience — and how these two types of memory processes both complement and trade-off with one another.

How does what we’ve experienced scaffold what we know?

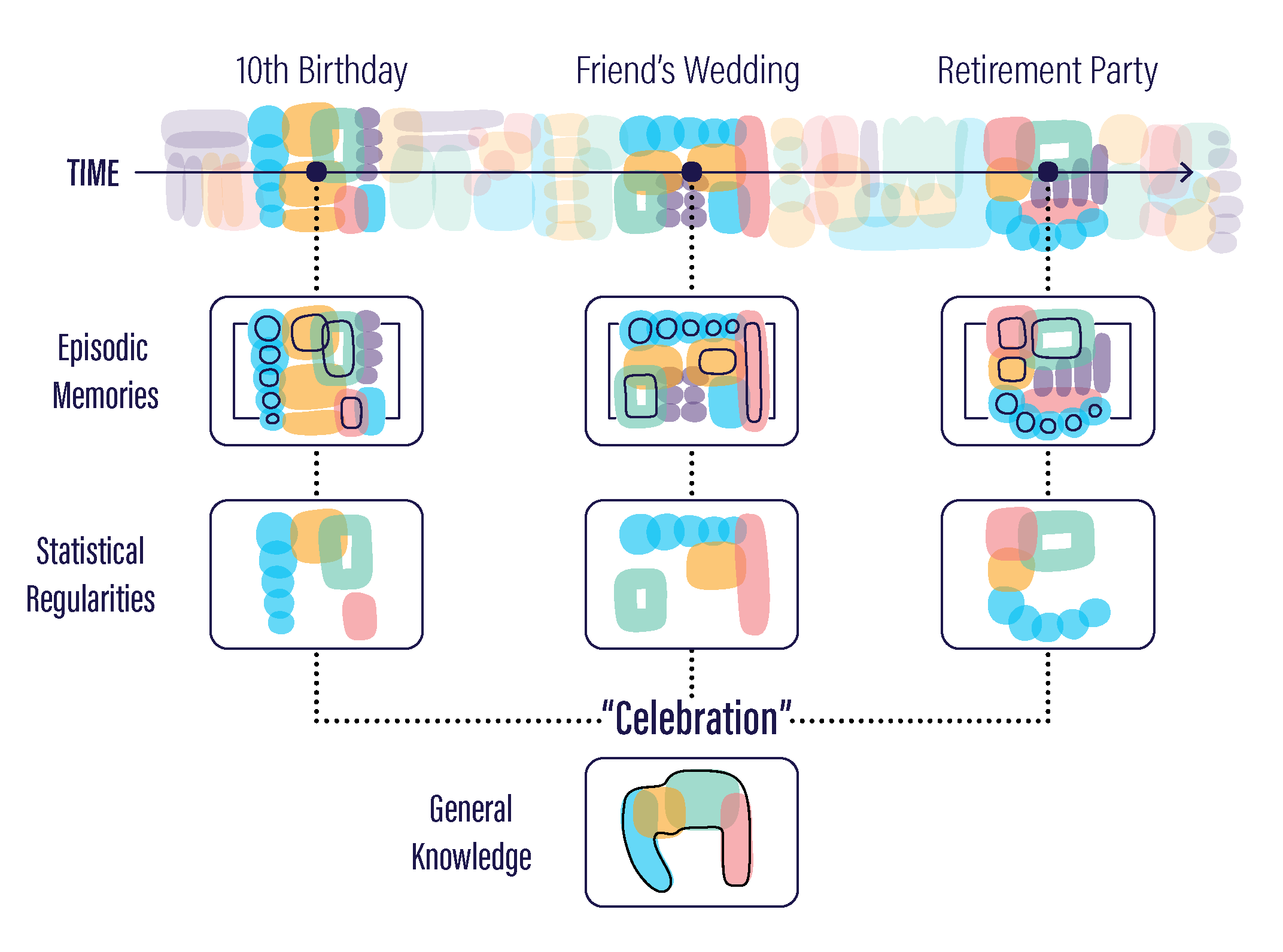

As we encounter new information in the world, we build and update our existing knowledge. For example, as you attend a birthday, wedding, or retirement party, you may update your concept of a ‘celebration’ – without over-writing your previous knowledge. We are interested in how we are able to build up this general knowledge about the world via a process called statistical learning, which requires that we integrate across related (episodic) memories in order to uncover structure and identify regularities in our environment. This process of building up and integrating new knowledge can occur quite quickly, but often occurs over the course of days or weeks, with sleep playing a fundamental role in bridging our memories over time.

How does what we know influence what we remember?

The hand-off between episodic memory and general knowledge is not uni-directional. Our general knowledge can also fundamentally shape the way we form new episodic memories. For example, general knowledge can facilitate episodic memory by helping us find the boundaries that demarcate and help organize events in memory (e.g., knowing that saying “goodbye” is a cue that a meeting is ending). However, general knowledge can also hinder episodic memory formation in other contexts: When we draw on our general past knowledge to make predictions about upcoming experiences, we may fail to encode the specific episodic details of that experience.

Ultimately, the goal of our work is to understand not only how we form new memories, but also why — seeking to understand the adaptive purpose of memory.

Related lines of research

Our memory systems are not isolated in the mind and brain; rather, our memories can influence and be influenced by a variety of other cognitive processes. We are also interested in understanding the broader interplay between memory and other aspects of experience.

-

When trying to recall when a specific memory occurred, you might find that it is surprisingly difficult to pinpoint the time of our memories. We are interested in understanding what cues we use to reconstruct time from our memories, with the goal of understanding why our sense of time so often diverges from reality.

Selected Works:

Sherman, B.E.*, DuBrow, S.*, Winawer, J. & Davachi, L. (2023). Mnemonic content and hippocampal patterns shape judgments of time. Psychological Science.[pdf]

Yates, T.S., Sherman, B.E. & Yousif, S.R. (2023). More than a moment: What does it mean to call something an ‘event’? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review.[pdf]

Yousif, S.R., Lee, S.H., Sherman, B.E. & Papafragou, A. (2024). Event representation at the scale of ordinary experience. Cognition.[pdf]

Sherman, B.E. & Yousif, S.R. (2025). An illusion of time caused by repeated experience. Psychological Science.[pdf]

-

Our daily lives are filled with acute stressors, which can powerfully influence what we encode into memory. Stress is often thought to be bad for episodic memory and the hippocampus, but some of our recent work has highlighted that this might not always be the case.

Selected Works:

Sherman, B.E., Huang, I., Wijaya, E.G., Turk-Browne, N.B. & Goldfarb, E.V. (2024). Acute stress effects on statistical learning and episodic memory. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. [pdf]

Sherman, B.E., Harris, B.B., Turk-Browne, N.B., Sinha, R. & Goldfarb, E.V. (2023). Hippocampal mechanisms support cortisol-induced memory enhancements. Journal of Neuroscience.[pdf]

Content developed in collaboration with Thoughtscape, Inc.